Pulse Market Insight #165 MAR 16 2018 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Indian Production Situation

In previous reports, I’ve looked at a number of factors that have caused this year’s depressed pulse markets. Prices have been under pressure and trade volumes have also been exceptionally slow. One reason for this situation has been the large production increases by exporting countries in the past two years, causing a buildup in supplies. There’s also been plenty of discussion about India’s response of erecting trade barriers. Now it’s time to turn the attention directly on India’s own role in this situation.

It’s not just larger pulse crops in North America and the Black Sea region that have weighed on markets. India’s own domestic production has also expanded sharply in the past two years. And this isn’t only because of ideal weather; conditions in India have been favourable but not extraordinary.

Much of the “blame” for the low price environment rests squarely on the Indian government. High pulse prices from a couple of years ago cause the Indian government to take steps to increase self-sufficiency and those actions have now come home to roost. The Indian government took a number of steps, such as subsidizing crop inputs and increasing minimum support prices, which encouraged farmers there to increase acreage and production.

When acreage increased and the weather cooperated, causing prices to drop, the government doubled down. They responded to farmers’ concerns by raising minimum support prices even higher, setting import quotas and imposing import tariffs, among other things. Some of these measures moved a few prices higher but most pulse prices continued to fall. Economics 101 says that trying to support prices artificially will send farmers the wrong signals to keep increasing production. In the end, that only drives prices even lower.

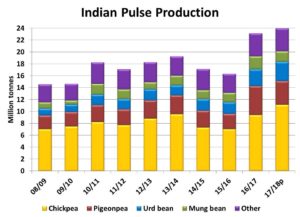

The chart above shows the Indian government’s latest projections for 2017/18 kharif and rabi pulse crops. The rabi crop estimates however are still far from certain. Even though the rabi harvest is nearly complete, these production numbers for chickpeas, lentils and peas (included in the “other” category) are simply based on average yields, not any sort of actual results. There’s a good chance the final production number will be lower than this estimate, because of lack of rainfall in the rabi season.

So what does this mean for pulse markets? The answer is that it depends on the type of pulses. For chickpeas, this estimate of 11 million tonnes would mean India is close to being self-sufficient. That’s likely why the Indian government has raised import tariffs on chickpeas to 60%, with rumours that it could go even higher.

For peas, Indian rabi production is also expected to rise somewhat but still will only provide about one third of India’s annual needs. As shown in the last Pulse Market Insight, India will need to return to the market for more yellow peas at some point later in 2018. And for green peas, which India doesn’t produce, imports haven’t slowed at all.

The lentil situation is similar to peas. This year’s production will likely be up but will only cover roughly half of India’s needs of red lentils. That means India will need to start importing red lentils again, likely in the late fall of 2018. India grows almost no green lentils and will need to keep importing those regardless.

The unfortunate aspect is that the Indian government is showing no signs of backing off from its misguided policies. Even so, the shortfalls in its domestic supplies of peas and lentils, especially greens, will allow trade to resume. It’s possible those tariffs could be reduced at some point but more likely, Indian prices will rise to the level that allows trades to occur. These developments will take a little time however and require patience from Canadian farmers.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.