Pulse Market Insight #169 MAY 25 2018 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

What’s the Outlook for India?

In the past few months, seemingly arbitrary (out of left field, if you will) decisions by the Indian government have caused a lot of turmoil and financial pain in pulse markets. Import tariffs, phytosanitary rulings and outright quantitative restrictions have all been used to limit the amount of pulses coming into the country.

The Indian government’s goal has been to artificially limit supplies and prop up domestic pulse prices to calm its angry farmers. And it’s really not concerned about angering farmers in other countries. Like it or not, India remains a key part of the pulse outlook, either through its presence or absence in the market. In this article, we’ll look at some possible developments and timelines that could help or hinder a return to normal trade.

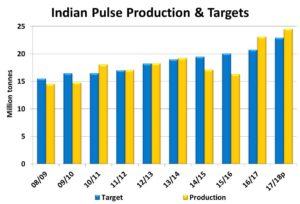

First, it’s important to recognize that India’s oversupply of pulses can’t really be blamed on imports. Policies by the Indian government, such as input subsidies and minimum support prices, have encouraged its own farmers to increase production to record levels for two straight years, well beyond its own targets. Favourable weather has helped too.

In its latest estimate of the 2017/18 pulse crops, the Indian government pegged total 2017/18 production at 24.5 million tonnes, 6% more than last year’s record. For rabi (winter) crop production, which includes chickpeas, lentils and peas, production was up 14% from a year ago. Those bigger crops, spurred on by its own policies, are the reason for the import restrictions imposed by the Indian government. Unfortunately, it may not admit that it’s at fault which could mean those policies will remain in place.

Breaking down the production forecast by type of pulse, we see that the 2017/18 chickpea crop is 33% larger than last year, and that has a couple of implications. While the majority of the chickpeas are desi types, India will also have a lot more kabuli chickpeas available for export and that will add weight to an already declining global market.

There wasn’t a specific production estimate for peas in the Indian crop report and it’s possible 2017/18 pea production is actually lower than last year. The problem for the pea market is that the record desi chickpea crop will limit India’s need for yellow pea imports which are the substitute for desi chickpeas. That’s the main reason why India has cut off pea imports, at least until the end of June. In addition, the risk of being on the wrong side of government policy has made traders reluctant to make deals beyond the end of June. In the meantime, the strength in Chinese demand has taken some pressure off the pea market.

The chart also shows that Indian lentil production is 1.5 million tonnes, a new record. This was an unexpectedly large result and could delay the return of India as a red lentil importer into the later part of 2018/19. It’s also possible the Indian government could add further import restrictions on lentils beyond the 33% import tariff. Unfortunately, other outlets besides India for Canadian red lentils are limited.

The key questions in all of this are, “How will this situation get resolved?” and “When will the pulse trade to India resume?”. Some have suggested the next Indian election in 2019 will mean the government can stop trying to buy farmers’ votes. More likely, it will resolve itself before that. The low pulse prices in India and elsewhere should discourage plantings in the upcoming kharif and the rabi seasons. The weather can also change the supply situation in a hurry. But as the production shift occurs and prices start to recover, the door will be opened to imports once again. At the end of the day, it will be prices and weather that resolve the issue, not the Indian government’s actions.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.