Pulse Market Insight #177 SEP 28 2018 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

What’s the Crystal Ball Forecast for Indian Trade?

One of the most frequent questions I get goes something like, “When will India start buying pulses again?” And the short answer is, “I don’t know.” Actions taken by the Indian government have been somewhat unpredictable and it’s hard to predict the unpredictable.

Even with the unclear future, I have a few hunches with respect to when the Indian government might finally ease its barriers on pulse imports. Unfortunately, I’m not very optimistic. In fact, the Indian government just extended its import ban on all types of peas until the end of December, not a real surprise.

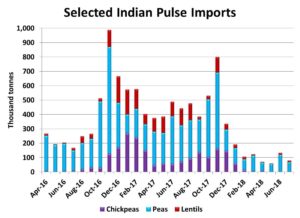

The chart below demonstrates the impact of the Indian import tariffs and other restrictions, with lentil and chickpea imports dwindling to negligible amounts for the past six months. Pea imports appear to be happening, although the scuttlebutt is that these are peas that were already sitting in limbo in Indian warehouses for a while, and the import paperwork was just processed later.

The Indian government has blamed the big import volumes in 2016 and 2017 for its decision to restrict further imports, but subsidized domestic production is the larger issue. This means the solution will need to come from India’s domestic situation.

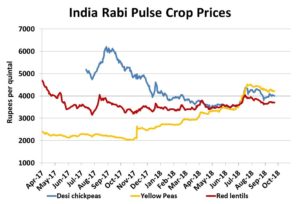

Currently, there are large inventories of pulses sitting in government and private warehouses and as long as they’re hanging over the market, the import barriers won’t be lowered. Prices are the strongest clue of actual supply levels and so far, there aren’t many optimistic signals. Lentil and chickpea prices had bumped up in July but have faded since then. These prices would likely have dropped further except that the government’s minimum support price (MSP) is just above the market and if prices fall too far, farmers will hold pulses in hopes of getting the MSP.

Pea prices have behaved a little differently, showing a solid rally this summer which signalled lower supplies, but eventually they also ran into a price ceiling too. There isn’t an MSP for peas but chickpeas acted as a cap on pea prices as the two pulses are substitutable. The point is that until these prices start to move higher in a meaningful way, the government will keep trying to limit supplies by restricting imports. And so far, that’s not happening.

There’s a widespread view that the Indian government is essentially trying to buy farmers’ votes by supporting prices through import restrictions (and other measures). The hope is that after the next election, the government will back away from its extremely costly farm support. This election will be held in April/May of 2019, so there’s some hope import barriers will be relaxed sometime after that. But in India, there’s no guarantee.

Ultimately, it may take a problem with the Indian crop to persuade the government to allow imports again. The current kharif (summer) crop is nearing maturity with few production issues, indicating no real supply issues. The next rabi (winter) crop, which includes chickpeas, peas and lentils, will start to be planted in November and harvested in Feb-Apr, so it’s far too soon to make any realistic predictions.

The bottom line is that the earliest resolution of these trade restrictions would be sometime in the spring or summer of 2019. The problem is that even this timeframe looks a little optimistic.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.