Pulse Market Insight #157 JAN 24 2020 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Lack of Clarity on Indian Outlook

Even though India’s importance as a pulse buyer has faded as it restricted imports, we can’t entirely ignore it either. The market dynamics for India are very diverse, requiring constant learning. And since the first import barriers were erected in late 2017, the ground continues to shift.

A key thing to understand about India is that the country is large with very different climatic regions. For pulses alone, Indian farmers plant 35-40 million acres of crops in a given year and while certain crops are concentrated in specific regions, others like chickpeas and pigeon peas are grown across wide areas of the country. As a result, it’s dangerous to attach too much weight to local weather reports (just like we don’t rewrite our Canadian crop forecasts because of rain/hail/drought/frost in one RM or County).

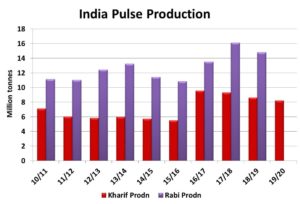

The reason for our caution is that we’ve seen some confusing news reports lately about the state of Indian pulse crops and the supposedly impacts on Canadian markets. Just as a refresher, there are two main pulse growing seasons in India, the summer or kharif season and the winter or rabi season.

The kharif season, which generally runs from June to October, is the smaller of the two for pulses. This season is also less relevant for Canadian pulses as the main crops are pigeon peas, urd beans and mung beans. While there is a partial linkage between pigeon peas and Indian demand for green lentils, kharif pulse crops have a limited (at best) impact on Canadian pulses.

The recent news reports about excessive rains and problems with Indian pulse production have been focused almost entirely on kharif crops, which were already harvested three months ago. It’s also worth noting that the much reported “rally” for Indian pigeon peas has largely fizzled, suggesting the crop losses were overstated. This is why it’s important to sift through the news reports to understand what’s really relevant.

Much more important for Canadian farmers is the rabi season, which began in November with the harvest starting in the next few weeks and finishing in early April. This is the country’s dry season and is when Indian farmers plant chickpeas, lentils and peas, far more relevant for Canadian markets.

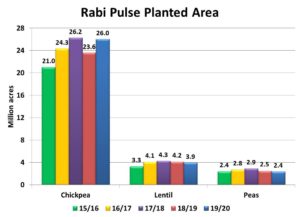

For 2019/20, Indian farmers have increased seeded area of chickpeas back up to near record levels. Acreage of lentils and peas is down a few percent from last year but hasn’t dropped too hard. More importantly, the heavy rains that caused some damage to the kharif pulse crops was actually beneficial for germination and emergence of the rabi crop. And because the rabi season is the drier time of the year, the above-average rain has been positive.

The bottom line is that the Indian rabi crop season is far more important in terms of demand for Canadian pulses and currently, there are no serious threats to the crop. Unfortunately, the result is that (with the possible exception of green peas), we don’t expect to see much easing in Indian import restrictions in the coming months.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.