Pulse Market Insight #174 NOV 6 2020 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Early Export Numbers Tell the Tale

This week, StatsCan released its latest monthly export data for September. Even though it’s already dated, it does provide clues about the market situation. For one thing, it gives an idea about where the demand is coming from and that allows us to look for more information in those destination markets, especially where data is scarce. Even though there’s a time lag between the StatsCan data and the current market, the export pace also helps understand how much crop will be left later in the marketing year.

Even a casual observer wouldn’t be surprised that Canadian pulse exports have jumped sharply. The price behaviour alone clearly showed that something extraordinary was going on. The weekly CGC export data was also showing heavy exports but doesn’t include container shipments, which are a sizable part of pulse crop exports.

For most pulse crops (other than chickpeas), old-crop supplies were running on fumes, which meant August exports were very low. Once the newly harvested 2020 crops became available, the situation turned around in a big way.

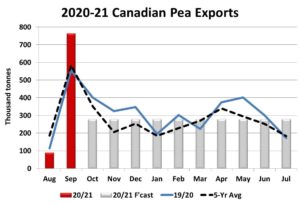

In September, pea exports hit 764,000 tonnes. While volumes normally peak in September, this was a new record, even better than a few years ago when India was buying as many Canadian peas as possible. This time around, it’s China doing all the buying, taking 85% of the September total. Earlier, we had expected a more measured purchase pace from China, but its need for peas is clearly much larger.

With this many peas already moving out in the first two months, it simply leaves less available for the rest of 2020/21. Even if the 2020 crop is a little larger than StatsCan’s last production estimate, the export pace definitely needs to slow down sharply. We already know that October exports will be above average again. It’s also clear that, even though prices normally start climbing in fall, this year’s sharp rally is the added clue that buyers are looking for more supplies than farmers are able/willing to sell.

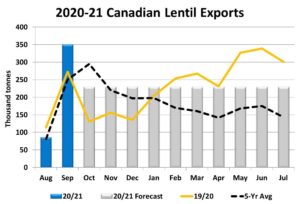

It’s a similar story for lentils, with a slow August and then a rapid pickup in September. The 350,000 tonnes exported in September wasn’t quite a new record for the month but was still well above average. In fact, for lentils, the normal peak doesn’t show up until October which we should see again in 2020/21, when that data becomes available.

In contrast to peas, heavy demand for lentils came from two major sources. India was the largest destination in September but Turkey was only slightly behind. This provides a signal about that the 2020 lentil crop in Turkey is on the smaller side of official estimates and is a clue that Turkish demand for the rest of the year will be strong.

The heavy pace early in the marketing year also means lentil supplies will get considerably tighter through the rest of 2020/21. And just like peas, very strong price signals have been confirming that outlook.

Because of the later harvest, chickpea exports don’t normally peak until October or November and that will likely be the case again in 2020/21. Even so, exports in September were just over 10,000 tonnes, the highest total for the month in a couple of years. That’s a hopeful signal that, after a couple of years of lacklustre exports, demand is picking up. Price signals for kabulis are the other clue of stronger demand.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.