Pulse Market Insight #138 MAR 15 2019 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

What to Make of India’s Pulse Crop Estimates?

The Indian rabi pulse crop outlook has been a source of keen interest over the past few months as Canadian farmers (and analysts) try to get a handle on market prospects for the rest of 2018/19 and the first half of 2019/20.

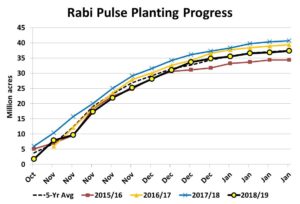

Just as a refresher, Indian farmers start to plant the pulse crops of most interest to Canada – peas, lentils and chickpeas – starting in late October and early November. Now the harvest is already underway. As the rabi (winter) growing season developed, a few things have become clearer.

Soil moisture reserves going into the rabi growing season were quite low and rainfall early in the season was also limited. The rabi season is the driest part of the year but rainfall amounts in most areas were still below normal. In the northern parts of the country, where peas and lentils are grown, sporadic rainfall fell and was beneficial for some areas. Moderate temperatures also helped mitigate the effects of the limited rainfall.

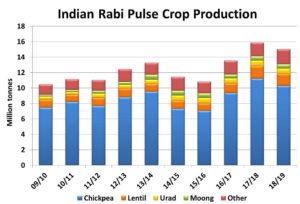

More importantly, Indian farmers planted fewer acres of pulses than the previous two years, which had been a high point. Together with strong yields, the increased acres in 2016/17 and 2017/18 had led to record pulse crops. The drop in 2018/19 acres, along with limited rainfall, should mean a considerably smaller rabi pulse crop. The first official estimates from the Indian Ag Ministry don’t necessarily reflect that view however.

While the government’s estimate for the total rabi pulse crop at 15.0 million tonnes is down 5.5% from last year, that doesn’t even match the 8% decline in acreage, let alone the reduced yields. Based on the official output estimate, yields would have to be even better than last year’s record yield, and that’s not realistic. Even if this year’s weather issues were less severe than reported earlier, expecting record yields this year is simply not in the cards. The actual rabi pulse output will almost certainly be 14.0 million tonnes or lower, which would be at least a 12% drop from last year. While not considered a crop failure, it will support larger Indian pulse imports next year.

India has largely been absent from Canadian pulse markets for well over a year and the industry here has been able to make some adjustments to this new reality, more so for peas than lentils. So the question is whether it’s important that India returns as a significant pulse buyer in 2019/20.

The main adjustment that’s been made to deal with the lack of Indian buying has been to reduce seeded area of peas and lentils in Canada (and elsewhere). Acreage of peas and lentils in 2019 will continue to be on the low side and that sets the stage for reduced supplies in 2019/20. That’s all well and good if India remains on the sidelines but if Indian pulse crops are small and its buying recovers, Canadian (and global) supplies could tighten a lot and drive the market higher. To a large degree, the size of the Indian crop will be the difference between a flat and a rallying market.