Pulse Market Insight #186 MAY 28 2021 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

How Will Canadian Markets be Affected by India?

India used to be front and centre when it came to all things pulses, but it seems to have faded a bit into the background, especially for the pea market. Import barriers have all but eliminated India as a pea buyer although it’s still quite important for lentils. Lately though, there’s been more market buzz about whether India will play a larger role again in pulse markets.

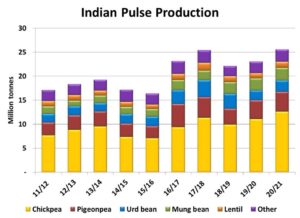

There are a few market signals that we watch when it comes to India’s pulse demand. First and foremost is the size of Indian pulse crops. This week, the Indian government released its latest estimate of 2020/21 production, with the rabi harvest wrapping up a few weeks ago. It raised its projection of total kharif and rabi pulse crops to 25.6 mln tonnes, up 11% from last year and a new record.

For lentils, the crop was pegged at 1.26 mln tonnes, up 15% from last year but down from the government’s earlier forecast. Unfortunately, India doesn’t report pea production separately but the category of “other rabi pulses” which includes peas was shown as 1.74 mln tonnes, 17% larger than last year. The biggest change was bumping up the chickpea crop (which influences demand for yellow peas) to 12.6 mln tonnes, a new record by a wide margin.

On their own, those production estimates would suggest India will not be in the market for many pulses this year. The “problem” is that these estimates are widely disputed, especially by sources within India. Most local analysts and traders would put the crop estimates 20-30% lower than the official numbers.

Our view is that price behaviour is a better indicator of actual supplies and prices seem to argue against most government estimates. Since the lentil harvest began in early February, Indian red lentil prices have risen over US$200 per tonne or 30%. The rally in desi chickpea prices hasn’t been quite as impressive and has since come off the highs but were up as much as 25% since harvest. That’s hardly a sign of a record crop. The one downer in the mix has been pea prices, which have fallen 25% from the record highs seen in late 2020. That’s a sign that domestic production actually increased this year.

The biggest factors affecting Canadian (and other countries’) pulse exports to India are its import barriers. Recently, the Indian government dropped all import restrictions for pigeon peas, mung beans and urd beans but these pulses have only an indirect impact on Canadian pulse markets. Even so, that’s an optimistic signal.

For lentils, the barrier is simply an import tariff of 33%. Last year, the Indian government temporarily lowered that tariff to 11%, which triggered a large surge of fresh trade and caused Canadian exports and prices to jump. The 2021 rally in Indian lentil prices has spawned much speculation that tariffs will be lowered again. Even though this hasn’t happened yet, we’re seeing reports of a jump in Canadian lentil exports, which has already boosted bids for both old-crop and new-crop. If the drop in tariffs actually happens, another round of export business is likely which would support prices further.

For peas and chickpeas, the picture isn’t quite as clear. For one thing, Indian pea prices have declined sharply on ideas of a larger rabi crop. The stall in the desi chickpea rally also means the government is under less pressure to control food inflation, at least for now. The import tariff for peas at 50% and 60% for chickpeas. But more important, quantitative restrictions apply to peas which are currently zero tonnes for yellows and only 50,000 tonnes for green peas. If these would change at some point, demand from another major importer besides China would significantly improve the price outlook for Canadian peas.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.