Pulse Market Insight #201 JAN 21 2022 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Exports Get Quieter as Prices Do Their Job

The terms “demand rationing” or more accurately “price rationing of demand” have been used frequently this year, largely caused by the impact of the drought in Canada and the northern US. It’s a basic economic concept that as prices rise, the number of buyers and the level of demand starts to shrink. Not much different than an auction sale, where there’s plenty of bidders when the price is low but, as the auctioneer gets the bids moving up, buyers keep moving to the sidelines until there’s only one left.

The 2021/22 marketing year has seen some very high (in some cases, record) prices for pulse crops. So it makes sense that the smaller supplies and higher prices would force some buyers out of the market. We see this change reflected in the trade data, with exports starting the year at a good clip but now fading fast.

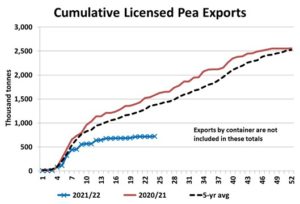

This chart shows Canadian pea exports that move through the elevator system (not including containers). For the first few weeks of the marketing year, exports were running at a pretty normal clip with the usual fall surge in movement. Prices for peas had already rallied in August but the solid Sep-Oct exports had already been traded well before the run-up.

Since then, pea exports (especially bulk shipments) have been much quieter, more noticeable since early November. China is the dominant destination for Canadian peas and in November, exports to that country dropped to only 18,000 tonnes, less than a tenth of its average monthly purchases. In the past few years, Bangladesh and Nepal have been sizable buyers but so far in 2021/22, have almost been shut out entirely. Other countries have also cut back their imports of Canadian peas.

The one exception to this downturn has been the US, which has boosted its pea imports from Canada, due to its own small crop. So far in 2021/22, Canada has exported 153,000 tonnes of peas to the US compared to only 21,000 tonnes in the same period last year. Buyers in the US, particularly processors, have been the most aggressive bidders for Canadian peas and are largely responsible for the record high yellow pea prices.

It’s worth noting though that there are limits to what US buyers are willing to pay for peas, especially with other sources still available. For example, in November the US imported 20,000 tonnes of peas from Ukraine, which is a highly unusual trade flow, on top of the 60,000 tonnes from Canada. More of those types of imports are quite likely in the months ahead as Black Sea peas remain at a large discount to Canadian peas.

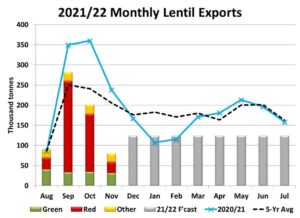

It’s a similar picture for lentils, with a strong shipping program the first three months of 2021/22, followed by a sharp drop-off in November. Some of Canada’s steadiest customers like India and Turkey took far fewer lentils in November, with the biggest declines in red lentil trade.

This doesn’t necessarily mean Canadian pulse exports won’t pick up again in the coming months, but a drop in prices might be needed to encourage trade. That’s the downside of demand rationing. Once the most aggressive buyers have filled their needs, the next set of demand won’t return until prices come off the highs. It’s also worth noting that trade in yellow peas and red lentils tends to be more sensitive to prices than green peas or green lentils.

Earlier this year, it seemed almost certain that Canadian pulse supplies would be drawn down to near zero stocks by the end of the year. There’s no question supplies will be very low for the rest of the year which will keep prices well above average. But if there isn’t a small recovery in export trade in the second half of 2021/22, there could be a few more peas and lentils left in Canada than we expected at the end of the year.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.