Pulse Market Insight #214 AUG 22 2022 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Outlook for Indian Pulse Demand

Even though India hasn’t been a major buyer of Canadian peas since 2016/17 (volumes have been only 10-12,000 tonnes the last two years), one of the most frequent questions I get is whether India will return as a buyer this year. Like everywhere else, there are rising concerns about food inflation in India and the question seems to stem from that issue.

Just as a refresher, back in late 2017, the Indian government imposed a 50% duty on pea imports. This was followed by quantitative restrictions that severely reduced the number of tonnes that could imported. This restriction was later refined to allow 75,000 tonnes of green pea imports per year. These barriers applied to peas from all origins, not just Canada.

Essentially, India’s government was trying to support pea prices for its own farmers at a time when pea imports had been weighing on the market. Keep in mind that at other times, the goal of the Indian government has been to keep food prices under control by allowing imports. The current concern about food inflation is the reason for wondering whether India will allow pea imports.

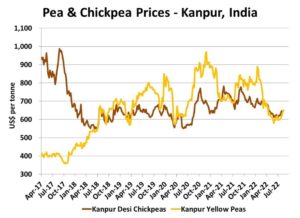

Since prices are the main driver of changes in import policy, it’s worth looking at the Indian market. The chart shows prices for yellow peas and desi chickpeas at Kanpur in north central India. Peas are frequently (but not always) a substitute for desi chickpeas. It shows the extremely low pea prices back in 2017, which triggered the import restrictions in the first place. Since then, prices more than doubled, with the peaks typically occurring in the Dec-Jan timeframe, 2-3 months before the Indian harvest.

While yellow pea and desi chickpea prices have ticked higher recently, those moves have been small and levels are nowhere near the highs of the past few years. This suggests the Indian government still has no pressing need to lower import restrictions. Of course, circumstances could change if the next rabi pulse crop harvested in early 2023 runs into problems. But that’s a distant possibility. India still allows 75,000 tonnes of green pea imports (with a 50% import tariff), so that remains a possibility.

The picture is different for lentils, particularly reds. The Indian government recently extended its zero tariff on lentil imports until March 2023, when its next lentil harvest would show up (import quantities have never been restricted). So this announcement didn’t really change trade prospects.

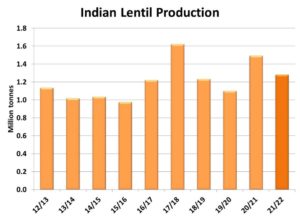

The Indian Ag Ministry just released its latest production estimate for the (almost all red) lentil crop harvested a few months ago. The crop was reduced to 1.28 mln tonnes from 1.44 mln earlier and is 14% smaller than last year. Keep in mind, some Indian observers think production has been overestimated the last few years.

On its own, a smaller lentil crop would be an optimistic signal for prospects of red lentil trade, but it hasn’t triggered higher prices in India. In fact, red lentil prices in India have lost US$120 per tonne since the harvest ended in April so there’s not an incentive to boost red lentil imports from Canada or Australia. Through the first six months of 2022, Indian lentil imports have averaged 30,000 per month and should pick up seasonally in the second half of the year.

There’s more optimism for Indian imports of green lentils. Green lentils are typically imported as a substitute for tur (pigeon peas), a summer crop. Tur production looks like it will drop considerably this year and Indian prices have been heading higher. It’s not a sure thing but could improve demand for Canadian green lentils later in 2022/23.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.