Pulse Market Insight #223 JAN 11 2023 | Producers | Pulse Market Insights

Indian Pulse Crop Situation

The winter growing season in India, also called the rabi season, has the strongest impact on Canadian pulse markets. That’s because it’s when Indian farmers are planting lentils, peas and chickpeas, crops that directly line up with Canadian production.

Planting of rabi crops usually starts in mid-October with the bulk of the acres planted in November. This year, planting got off to a strong start, helped by favourable moisture conditions at the tail end of the summer (kharif) season. For the three main pulse crops we’re looking at, Indian farmers have responded differently with their planting decisions.

Every year, the Indian government issues Minimum Support Prices for major crops, which includes chickpeas (gram) and lentils, but not peas. A few months ago, the MSP for desi chickpeas was raised by 2% while the MSP for lentils was bumped up by 9%. The MSP isn’t the only factor affecting farmers’ decisions. Market prices in India for desi chickpeas and peas are closer to the low end of the past few years while red lentil prices look a bit better.

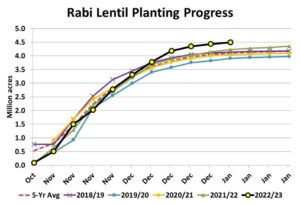

The combination of MSPs and market prices have encouraged Indian farmers to add more lentil plantings, at 4.5 mln acres by the end of January. That’s 6% more than last year and 9% above the 5-year average. In contrast, pea plantings are at 2.3 mln acres, 4% less than last year and 6% below average. The dominant rabi pulse crop is chickpeas, with Indian farmers planting 26.6 mln acres so far, 1% less than last year but 4% above average.

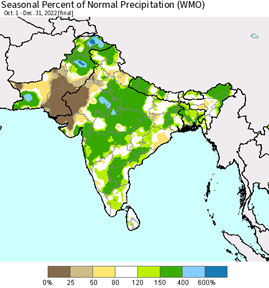

Seeded area is only half of the crop outlook though. The rabi season is also the drier season of the year. Rainfall at the end of the summer season is critical to establish soil moisture for the winter crop and this year, those rains have been plentiful and helped get the crop off to a good start.

Since the beginning of the rabi season, rainfall has been above average for much of the country. Most of the lentil, pea and kabuli chickpea acres are in the north-central part of the country, which has had the most favourable rains. Desi chickpeas are scattered more broadly around the country, but most have received good rainfall.

The critical time of year for pulse crop development is January, when moisture is most critical and temperatures can fluctuate widely. For the most part, Indian pulses are in good shape and are less vulnerable to yield losses.

If that favourable situation continues, it suggests India could need fewer lentil imports once the harvest is complete in late March or early April. For peas and chickpeas, India already has very large barriers to imports and a decent sized crop of its own means those restrictions would likely remain in place. That’s not really good news, but it’s important to stay informed.

Pulse Market Insight provides market commentary from Chuck Penner of LeftField Commodity Research to help with pulse marketing decisions.